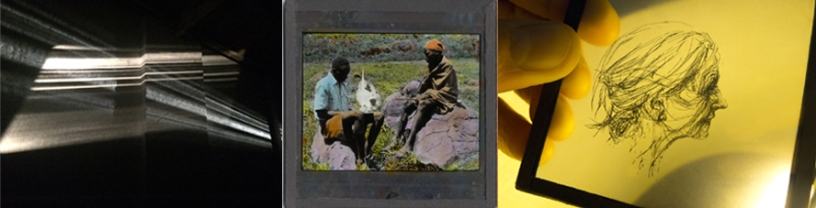

Sonia Overall is currently the Resident Armchair Artist at The Beaney in Canterbury.

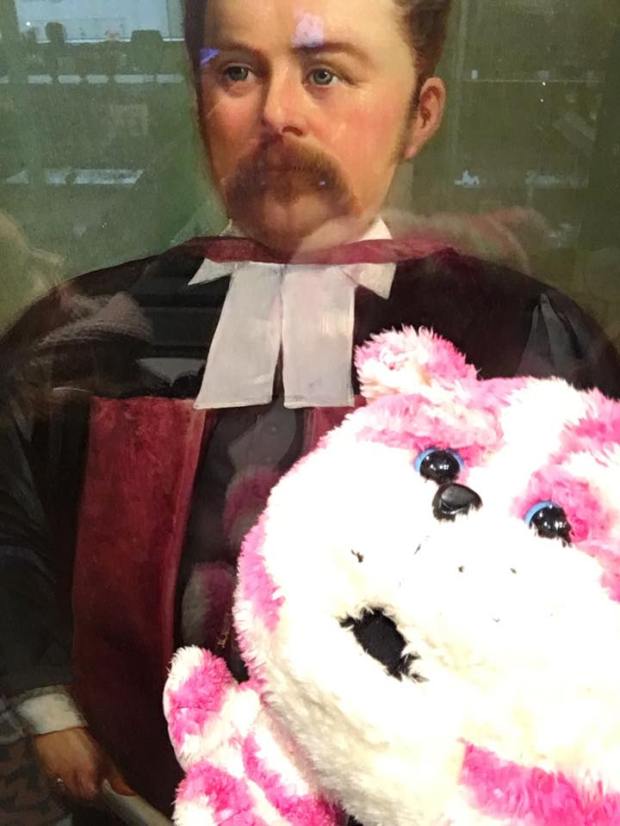

One of the chief attractions of the armchair artist opportunity for me was meeting previous residents Jill Holder and Bob Lamoon. Their oversized homage to the rook in the red coat, exhibited in the Front Room, continues to haunt me.

The original rook is perched in the Colour & Camouflage collection. Here he is surrounded by monochrome birds: a black cough, pygmy cormorant, common scoter and a dull, dun-coloured blackbird. Even the nearby Australian pygmy goose is a study in black, white and grey: the green sheen of wing feather, hinting at the glamour of abalone shell, turned modestly to the wall. By contrast, the neighbours in the next cabinet are an explosion in emerald, cobalt and acid yellow: toucan, quetzal, macaw, blue rollers with bright bead eyes. These birds display the mineral depth of their plumage beside lumps of lapis, azurite, malachite and jade.

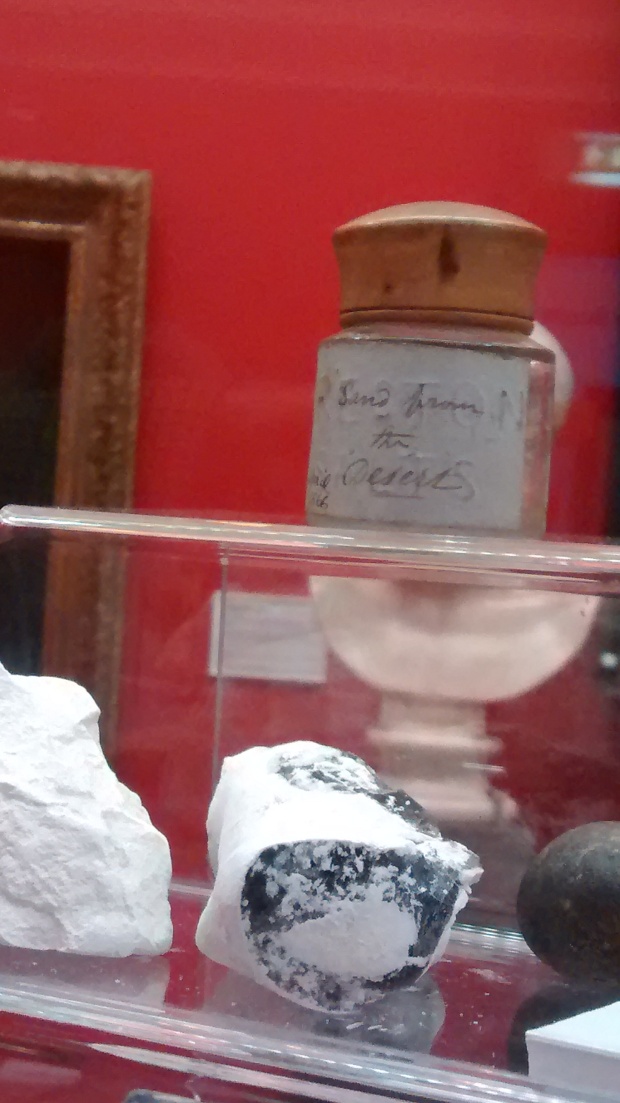

The rook is a bird of one colour dressed in another: borrowed plumage, an upstart crow beautified with our feathers, or rather, dressed by us in an apron of cloth. There’s a common theme here: one object dancing to the tune of another, more glamorous, companion, taking on name and aspect. The ‘potato stone with red agate’ is raised above humble tuber-lookalikes with its cross-section of ruby flesh. The bland beige ‘potstone’ takes on chips and streaks of terracotta. The rook’s red coat may have marked it out, but this proved its downfall: wounded and tended to by children; dressed and released; rejected for its otherness by the avian community; shot by a famer as an easy target.

So where does this take me? I notice red splashes everywhere. Incidental reds in gallery furnishings: fire extinguishers, sofa, explorer signs. A visitor’s scarlet lipstick and a child’s wet raincoat. Reds saturate the collections: James Beaney’s burgundy velvet, wool squares on a Sudanese tunic, garnet glaze on an Emperor’s porcelain vase. Symbolic reds: cloth gathered around the knights about to spill Beckett’s blood. Sun-shot clouds above a Canterbury angel. Solomon in regal judgement. The walls of the Materials and Masters room are a rich salon red. Peter Firmin’s slatey prints are off-set by bright red sugar paper. The cakes in the café are displayed on a toffee-apple-red counter. But I keep going back to the rook, his borrowed finery now reduced to a tatty rust-coloured tabard; the red claws and hooked beak of the black cough, now missing a glass eye; the zebra piping on the great northern diver’s neck.

The rook brings to mind stories of befriending birds. Another damaged rook was lucky enough to be nursed by a friend of mine who called him Corvus and took him out for walks in a basket. As children, my brother and I looked after a crow with a broken wing, keeping it away from cats in a cold-frame at the bottom of the garden. Growing up on a farm, my father raised various abandoned creatures. One was an injured jackdaw – Jack – who he raised to maturity. The inside of Jack’s mouth had been damaged, giving him a distinctive call. Every year the jackdaw would come to visit, sitting on the same branch of a favourite tree on the border of field and cottages, calling to my father in his trademark tones.

While these birds suffer our tenderness, they remain wild, and I wonder if something of that wildness intensifies them, gives us impressions of them in stronger colours. Fur and feather fade on taxidermy specimens, the red of fox and squirrel turning russet-brown and sand. But it isn’t just time that does this: these cased animals have become objects for our scrutiny. They lack the vibrancy of animation. When I recall encounters with wild creatures they are brighter and larger than their stuffed companions. A fox crossing the road late at night, lit by streetlamps. Another, strawberry-and-cream in strong sunlight, spotted from a motorway, dancing in an open field. A squirrel hurtling across forest paths; a sudden stampede of red deer. The same could be said of the rook, close at hand, turning leaf litter in search of food: oil-slick of feathers, hugeness of grey knifed beak, mercury-quick eyes and rolling gait. No added colours necessary.